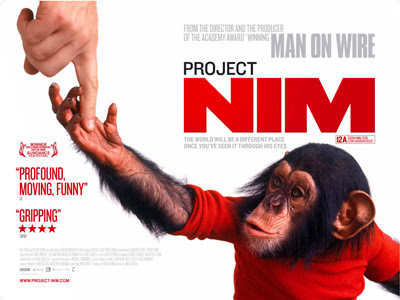

New Forest Film Festival: Project Nim: Responsibility and Mind

The New Forest Film Festival's screening of the excellent documentary Project Nim featured the added value of introduction and then post viewing Q&A with Mike Colbourne, senior keeper at Dorset's Monkey World Ape Rescue Centre, mediated by Film Festival Organizer Linda Ruth Williams. Professor of Film at Southampton University. The film's story of the chimp Nim, taught to sign and used for a spurious experiment to raise him as if he were human, in the context of an extended human family, becomes a vision of a hell paved with good intentions. An absorbing thoughtful film which further elevates the pedigree of director James Marsh (Man on Wire).

There are some slightly artificial illustrative "recreations" that fill gaps in the archive footage, but these do nothing to detract from the air of verisimilitude, whilst giving us the blessed relief of a slight remove from the frankly grim material, a tragedy of errors born of arrogance and self delusion as Nim's "me generation" keepers play an increasingly harmful game of pass the parcel with the hapless animal. Indeed, even the person who comes off best in the film, to the extent that many in the audience consider him the hero of the story, is irresponsible enough to share his recreational drugs with the chimp. Monkey see, monkey dude.

Primate advocates are always eager to stress the notion that the apes are our "closest relatives" in the animal kingdom. This is meant to elicit sympathy, but it also is an own goal because it supports the delusion that we can understand them on human terms. This is a mistake repeated many times throughout the film.

A would be saviour of Nim removes him from one appalling situation, but installs him in isolation, an ordeal for a social animal. A violent incident occurs when a person from much earlier in Nim's story visits and unwisely enters Nim's enclosure. Everyone assumes the attack is based on recognition and a concomitant emotional outburst. In the post film Q&A the primate keeper ascribes it to "frustration". What happens could as easily be a reaction to an intruder on Nim's solitary territory. The problem is we can't fathom Nim's motives, and every time those in his life presume to do so, as well as us, after the fact, he is done a great disservice.

It is not unusual for us to project our own way of thinking onto the actions of animals. We do this all the time, not just with animals, but as we interact with each other, this is called the Theory of Mind (a very good article about how this applies to how we treat our dogs can be found here: slate.com Do Dogs Think?). This is always bound to cause problems as we assume the needs and values of those whose minds we imagine. Nim's story is fraught with the presumptions of his keepers, particularly the notion that just by dressing him up and "raising" him as human, he'd automatically become more like us.

The other problem that Nim encounters is that many of his "benefactors" treat him as a pet. The guest keeper does use the discussion as a platform to highlight a petition to call for a government debate on primate keeping, strengthen the legislation on the control and monitoring of primates in pet ownership (Primates as Pets Petition). Their aim is not to ban ownership, which would drive the trade underground, but to better regulate and institute a proper regime of checks of owners and animal living conditions. In old regime, anyone could own wild animals as pets. The wild animal licensing laws stopped much pet ownership except strangely, smaller primates, which have the same problems of maltreatment. Most primates are social animals, removing them to a human context isolates them and psychologically impacts on them. The fundamental disconnect occurs when owners fail to understand all of the animal's requirements.

This problem is common to owners of standard pets. As a dog owner, and infrequent breeder, whose wife does assessments for a spaniel rescue, I'm used to vetting potential pet owners. This process may seem as intense as an adoption, but it is as important to determine whether they're prepared to take on the consequences of caring, keeping and training their animal throughout its life. When acting as a breeder, the conversation provides scrutiny in both directions. We wouldn't like to place puppies with people who aren't asking the right questions about the needs of their charges.

Many have well meaning but cavalier attitude towards pets, as toys, accessories, or as automatic companions with no inherent needs. For whatever love people may profess towards animals, however deeply felt, we're humans, and we just don't think things through. That cute puppy may be encouraged to jump up, sit on furniture or play tug of war with toys and leads, but when fully grown will suddenly be expected to desist from these behaviours; that sweet chimp approaching adulthood may casually kill other pets and chew half your face off and has the strength to easily maim or kill. That the trajectory of each lifecycle is known and predictable is either wilfully ignored, confounded by irresponsible ignorance or (in the case of photographers who defang chimps for a career in cute "family" photos) managed with intentional mutilation or euthanasia.

Back in the 1980s I had a friend who had looked forward to being a research scientist, had trained for it, and had his first job in a university medical research lab. In an adjacent lab studies were being done with primates, looking into the effect of collisions on the neck and spine. For these simulations chimps and orangutans were accelerated at walls and static objects at various angles and speeds. The injured apes were then diagnosed for how their musculature and vertebrae coped with these injuries. Just being in proximity to this extremity of ethical science made my friend rethink his choice of career. He spoke to me of the flawed grant system which encouraged studies to be proposed almost purely for the sake of generating grant money. Careers constructed around innovative methods of harm with the furthering of science an almost secondary consideration.

I myself am a queasy fencesitter about animal testing, particularly as a son of a Parkinson's sufferer. Mike Colbourne in his introduction was quite honest about diabetes and other conditions that he has that require treatments that most likely were tested on primates in the past, but he pointed out what he has seen of the sharp end, the ex-lab primates that have come to his care physically and mentally distraught. That testing could be used as a last resort only for arguably vital research when other methods are exhausted, is a door that may be left open.

We must remain mindful of our responsibility to the animals, whatever use we put them to. It is responsibility thought through, responsibility acted upon and responsibility seen through, not opposable thumbs, language, abstract thinking, nor other self congratulatory virtues that may truly elevate us amongst the animals, however closely related we may be.

There are some slightly artificial illustrative "recreations" that fill gaps in the archive footage, but these do nothing to detract from the air of verisimilitude, whilst giving us the blessed relief of a slight remove from the frankly grim material, a tragedy of errors born of arrogance and self delusion as Nim's "me generation" keepers play an increasingly harmful game of pass the parcel with the hapless animal. Indeed, even the person who comes off best in the film, to the extent that many in the audience consider him the hero of the story, is irresponsible enough to share his recreational drugs with the chimp. Monkey see, monkey dude.

Primate advocates are always eager to stress the notion that the apes are our "closest relatives" in the animal kingdom. This is meant to elicit sympathy, but it also is an own goal because it supports the delusion that we can understand them on human terms. This is a mistake repeated many times throughout the film.

A would be saviour of Nim removes him from one appalling situation, but installs him in isolation, an ordeal for a social animal. A violent incident occurs when a person from much earlier in Nim's story visits and unwisely enters Nim's enclosure. Everyone assumes the attack is based on recognition and a concomitant emotional outburst. In the post film Q&A the primate keeper ascribes it to "frustration". What happens could as easily be a reaction to an intruder on Nim's solitary territory. The problem is we can't fathom Nim's motives, and every time those in his life presume to do so, as well as us, after the fact, he is done a great disservice.

It is not unusual for us to project our own way of thinking onto the actions of animals. We do this all the time, not just with animals, but as we interact with each other, this is called the Theory of Mind (a very good article about how this applies to how we treat our dogs can be found here: slate.com Do Dogs Think?). This is always bound to cause problems as we assume the needs and values of those whose minds we imagine. Nim's story is fraught with the presumptions of his keepers, particularly the notion that just by dressing him up and "raising" him as human, he'd automatically become more like us.

The other problem that Nim encounters is that many of his "benefactors" treat him as a pet. The guest keeper does use the discussion as a platform to highlight a petition to call for a government debate on primate keeping, strengthen the legislation on the control and monitoring of primates in pet ownership (Primates as Pets Petition). Their aim is not to ban ownership, which would drive the trade underground, but to better regulate and institute a proper regime of checks of owners and animal living conditions. In old regime, anyone could own wild animals as pets. The wild animal licensing laws stopped much pet ownership except strangely, smaller primates, which have the same problems of maltreatment. Most primates are social animals, removing them to a human context isolates them and psychologically impacts on them. The fundamental disconnect occurs when owners fail to understand all of the animal's requirements.

This problem is common to owners of standard pets. As a dog owner, and infrequent breeder, whose wife does assessments for a spaniel rescue, I'm used to vetting potential pet owners. This process may seem as intense as an adoption, but it is as important to determine whether they're prepared to take on the consequences of caring, keeping and training their animal throughout its life. When acting as a breeder, the conversation provides scrutiny in both directions. We wouldn't like to place puppies with people who aren't asking the right questions about the needs of their charges.

Many have well meaning but cavalier attitude towards pets, as toys, accessories, or as automatic companions with no inherent needs. For whatever love people may profess towards animals, however deeply felt, we're humans, and we just don't think things through. That cute puppy may be encouraged to jump up, sit on furniture or play tug of war with toys and leads, but when fully grown will suddenly be expected to desist from these behaviours; that sweet chimp approaching adulthood may casually kill other pets and chew half your face off and has the strength to easily maim or kill. That the trajectory of each lifecycle is known and predictable is either wilfully ignored, confounded by irresponsible ignorance or (in the case of photographers who defang chimps for a career in cute "family" photos) managed with intentional mutilation or euthanasia.

Back in the 1980s I had a friend who had looked forward to being a research scientist, had trained for it, and had his first job in a university medical research lab. In an adjacent lab studies were being done with primates, looking into the effect of collisions on the neck and spine. For these simulations chimps and orangutans were accelerated at walls and static objects at various angles and speeds. The injured apes were then diagnosed for how their musculature and vertebrae coped with these injuries. Just being in proximity to this extremity of ethical science made my friend rethink his choice of career. He spoke to me of the flawed grant system which encouraged studies to be proposed almost purely for the sake of generating grant money. Careers constructed around innovative methods of harm with the furthering of science an almost secondary consideration.

I myself am a queasy fencesitter about animal testing, particularly as a son of a Parkinson's sufferer. Mike Colbourne in his introduction was quite honest about diabetes and other conditions that he has that require treatments that most likely were tested on primates in the past, but he pointed out what he has seen of the sharp end, the ex-lab primates that have come to his care physically and mentally distraught. That testing could be used as a last resort only for arguably vital research when other methods are exhausted, is a door that may be left open.

We must remain mindful of our responsibility to the animals, whatever use we put them to. It is responsibility thought through, responsibility acted upon and responsibility seen through, not opposable thumbs, language, abstract thinking, nor other self congratulatory virtues that may truly elevate us amongst the animals, however closely related we may be.

Labels: Life Irritates Art, New Forest Film Festival, Reviews

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home